At the museum, you should see this

ONE OBJECT

Today’s art object in London is not about London at all, but rather,

19th-century Paris, the world’s first modern city

Through the traumatic years of the French Revolutionary Era, the crumbling medieval city of Paris was on the brink of collapse.

In 1845 the French social reformer Victor Considerant wrote:

"Paris is an immense workshop of putrefaction, where misery, pestilence and sickness work in concert, where sunlight and air rarely penetrate. Paris is a terrible place where plants shrivel and perish, and where, of seven small infants, four die during the course of the year."

The center of Paris was overcrowded, dark, dangerous, and unhealthy. The city was also a cradle of discontent and revolution; between 1830 and 1848, seven armed uprisings and revolts erupted in the center of Paris.

France’s first elected president, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte tapped civic engineer, Georges Hausmann to reimagine Paris as the center of modern industry.

Haussmann’s new Paris started from the bottom up. In 1850, 372 miles of modernized subterranean sewer lines were installed below ground.

Author Victor Hugo exclaimed,

““The present sewer is a beautiful sewer; the pure style reigns there…”

You can tour the underground 'sewer city' on your next visit to Paris.

Next, entire neighborhoods were bulldozed and new, wide boulevards radiated from the city center to ensure easy circulation of traffic.

The characteristic residential apartments were made under Haussmann’s watch, along with industrial innovations such as railway stations and an underground metro.

Caillabotte, La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage, 1878

Caillabotte, La Rue Halévy, vue du sixième étage, 1878

Haussmann’s vision of Paris was one of social intersections—in his Paris, a park is never more than a 10-minute walk. New cultural centers, such as the Paris Opera House, encourage public gatherings.

Sculptural Group, La Danse, at the Paris Opera House.

Sculptural Group, La Danse, at the Paris Opera House.

And the gas lighting and commercial hubs throughout the city introduced a type of nightlife that was virtually unknown before this time.

Photo by Michelle Williams on Unsplash

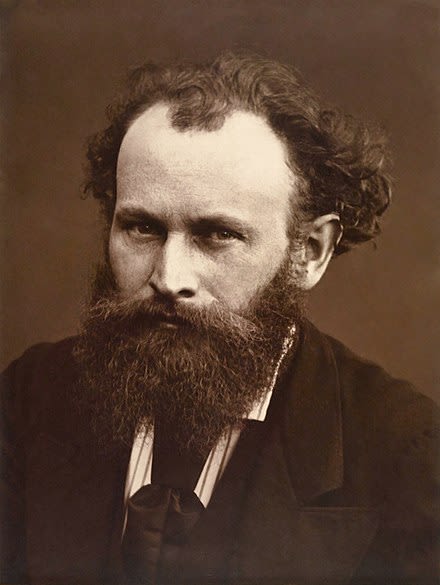

Edouard Manet grew up in the rubble of this construction era in Paris. He came of age in 1860s, trained by traditional academics to paint heroic history paintings and mythological scenes.

Manet could not keep painting from the past, when the vision of the future seemed to rise all around him in the world’s first modern city.

Manet's body of work boldly stepped away from the traditional academic subjects of historical heroes and mythological nudes, opting instead to boldly paint modern people in modern spaces.

Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe

Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets

Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets

The Monet Family

The Monet Family

The Fifer

The Fifer

Manet, Bar at the Folies Berger, 1869

Manet, Bar at the Folies Berger, 1869

This large-scale painting reflects Manet’s signature style:

The barmaid’s black dress and Manet’s sketchy brushstrokes flatten the space—we aren’t tricked to believe that this is a 3-d space.

If we follow the gold band that divides the painting, we conclude that there is a large mirror behind the bar maid. We can see what is in the reflected space, presumably behind where you and I are standing.

Manet has now placed me at the bar, and I am next in line to order up the pleasures of the evening. On this flat, 2-d painting, Manet has placed me right inside the 19th-century Parisian Café-Concert.

Looking in the mirror, we see the evening’s entertainment:

The feet of the trapeze artist hang from above.

Strangers see and are seen by each other, a spectacle unto itself!

Following the mirror, we see spatial distortion. The angles do not line up with the bar maid before us.

Also, the reflected bar maid is engaged, leaning eagerly toward her customer and listening to his order for the night’s indulgences

(Is that me? The mustachioed man in the top hat?).

The bar maid that we see before us is not the enthusiastic reflection, but rather, a working woman in a bustling city. Her face carries the gaze of a city mask—a face that hides the weariness and alienation that comes with city life, a protection from unwanted advances from customers?

When Manet creates a disconnect between the bar maid and her reflection, perhaps he recognizes the disconnect that there is between the promises of living in a modern world, with promises of endless, ever-present pleasures, and the reality that can never live up to that dream.