If you are going to the museum, you should see this

ONE OBJECT

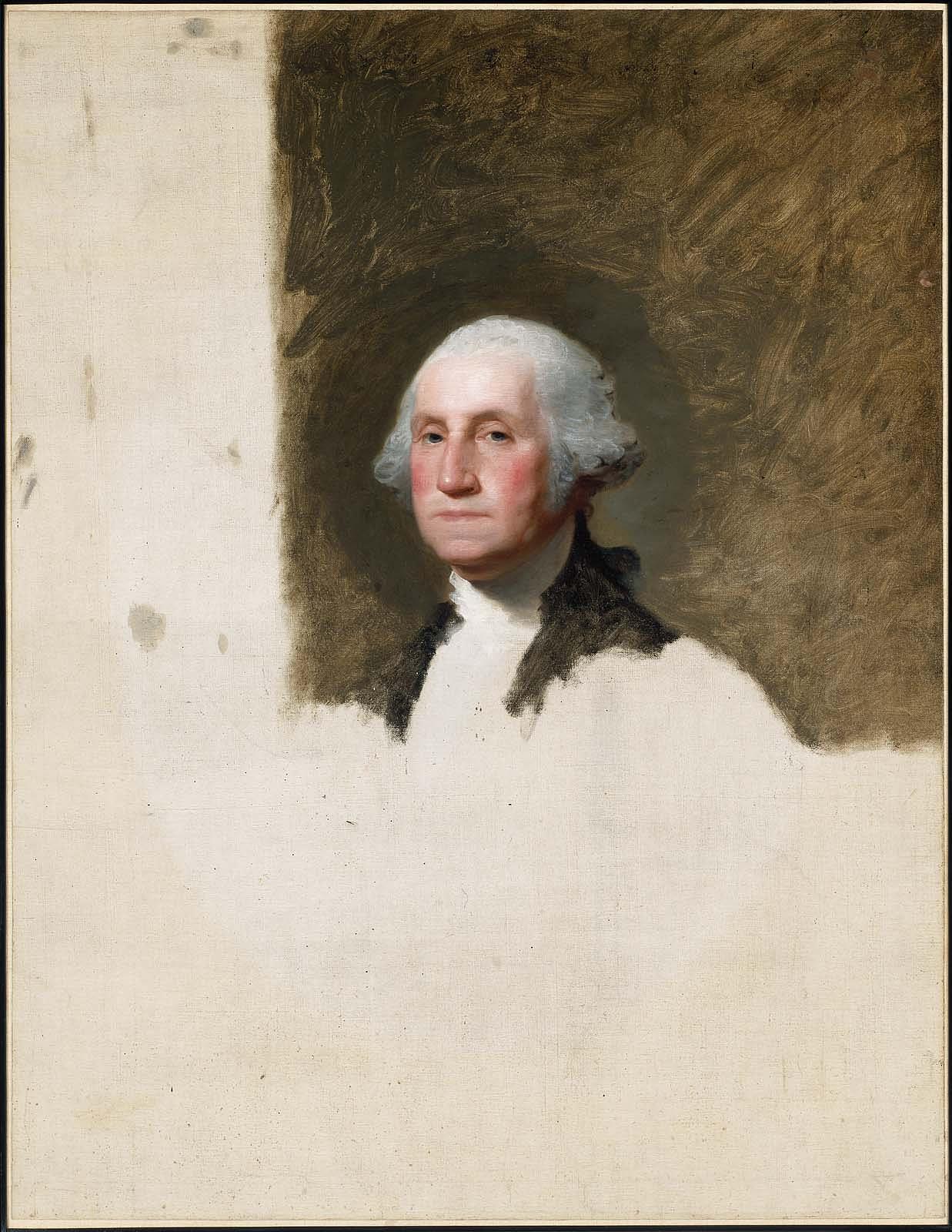

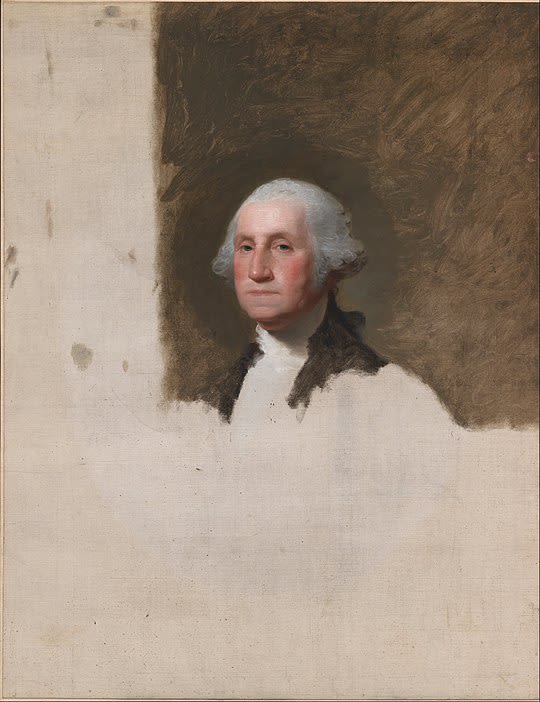

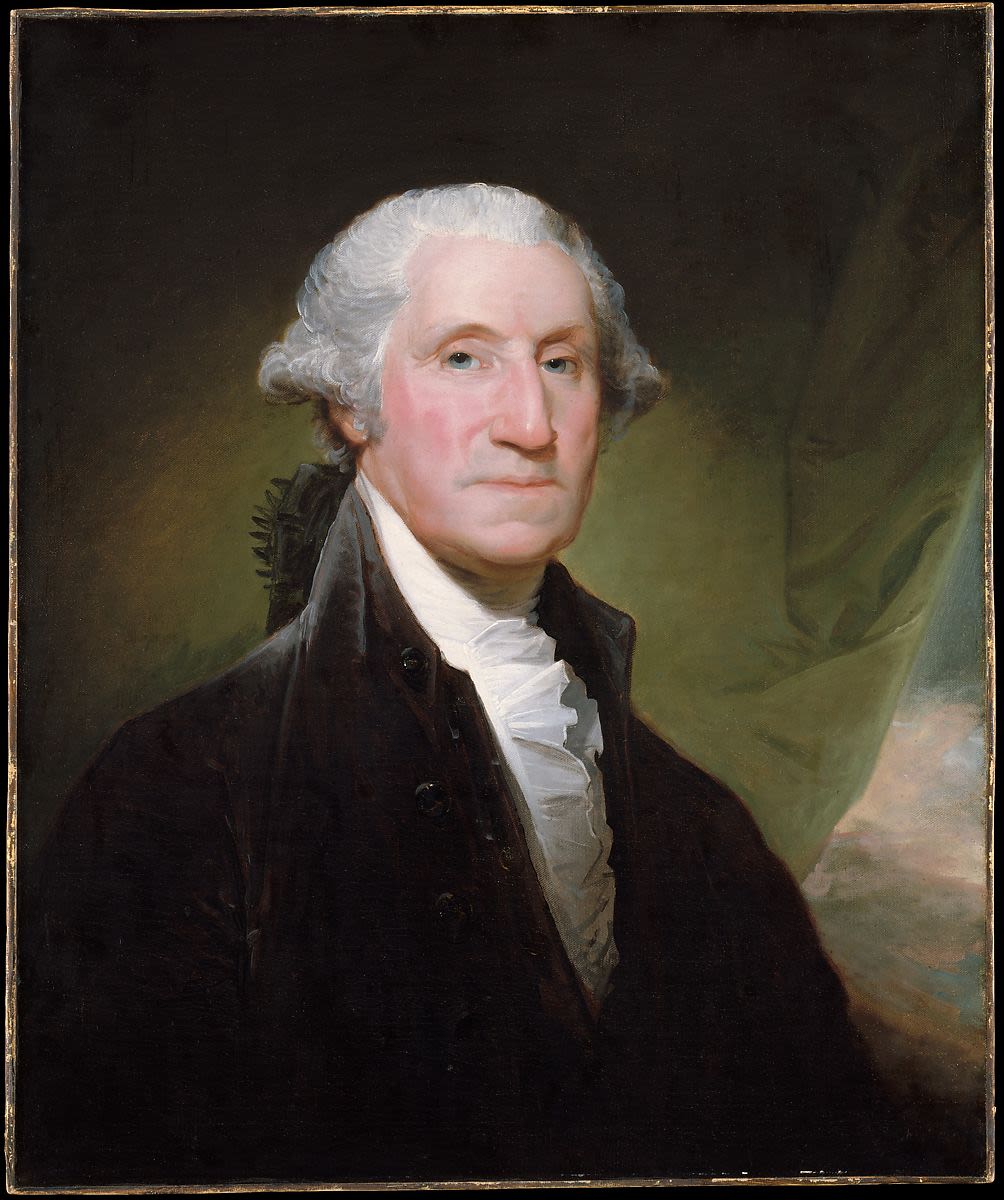

This portrait is a paradox.

The intense gaze from Washington’s eyes, the locked jaw, even the contours of Washington’s wig are instantly recognizable to us.

This exact face lives on in our pockets and wallets. Known as the Athenaeum Portrait, the mirror image of this likeness became the engraved face on the US $1 bill.

The chiseled features of Washington’s head are a strange contrast to the broadly painted brushstrokes of the brown background.

And then….nothing!

The painting stops, leaving the bulk of the space as rough, unprimed canvas.

In 1796, George Washington sat for the artist, Gilbert Stuart, known as “the unofficial portraitist of a new nation.” Washington was 65 years old, immortalized by Stuart in this painting just three years before his death.

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828)

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828)

Stuart, a Rhode-Island born patriot, trained and experienced great success as an artist in England at the Royal Art Academy. Upon his return, Stuart worked prolifically, painting 1000 influential political and cultural figures in his lifetime.

Stuart skills as a portraitist went beyond the paintbrush—while he worked away on the canvas, his charisma kept his sitters at ease.

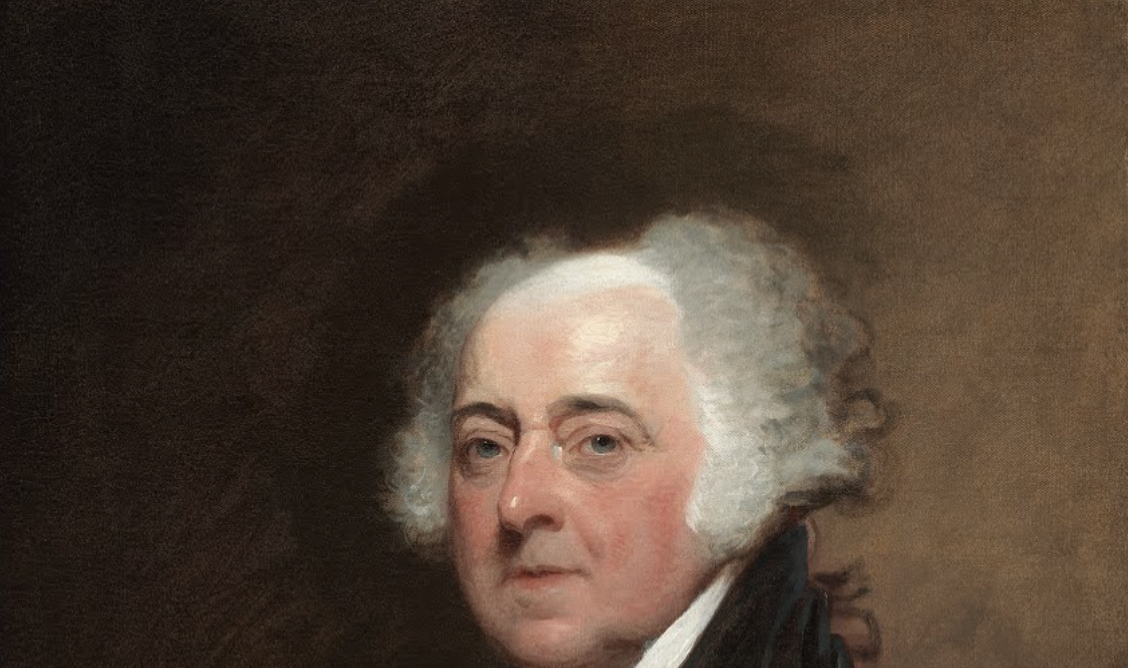

According to John Adams:

Speaking generally, no penance is like having one's picture done. You must sit in a constrained and unnatural position, which is a trial to the temper.

But I should like to sit for Stuart from the first of January to the last of December,

for he lets me do just what I please, and keeps me constantly amused by his conversation.

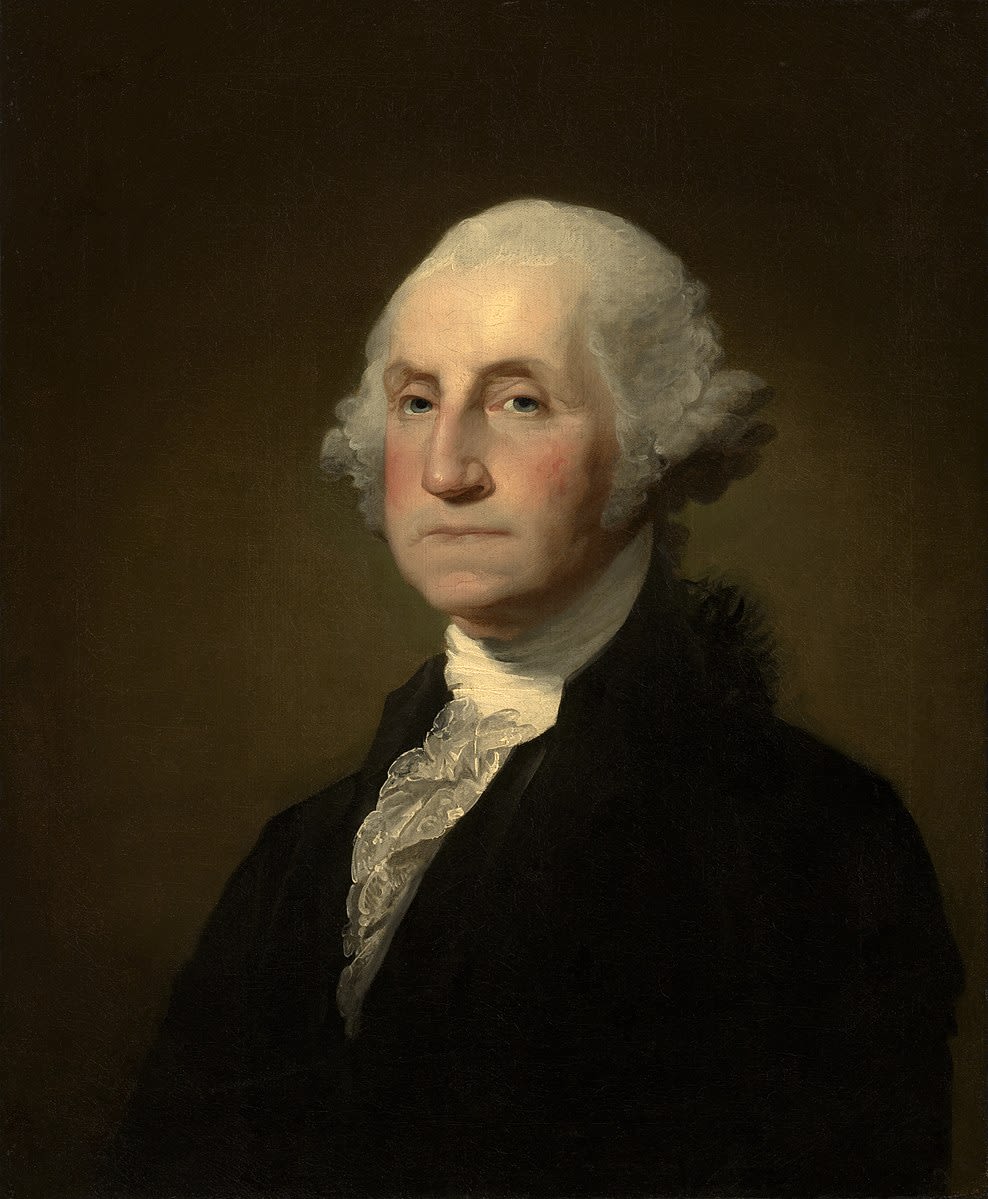

George Washington’s reputation, while reputable in life, was elevated to a saintly sphere after his death in 1799. The cultural reverence for Washington in the early 19th century mimicked religious devotion.

As demand for more Washington portraits grew, Stuart and others relied on the Athenaeum Portrait to recall Washington’s exact features.

Stuart called this painting his “$100”. This painting acted as a prototype, the blueprint for other paintings and visual reproductions of Washington, which Stuart famously sold at a $100 a piece.

The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons - 1789

The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons - 1789

The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte - 1821

The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte - 1821

The Death of Socrates - 1787

The Death of Socrates - 1787

The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis - 1818

The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis - 1818

Napoleon at the Saint-Bernard Pass - 1801

Napoleon at the Saint-Bernard Pass - 1801

While Stuart’s portraits exude a mood of respectable dignity, Stuart was known as one who spent money as fervently as he made it. Several times in his life, Stuart found himself on the run from debtor’s prison and he left his large family with crushing debt.

No doubt, this “$100” was a welcome way for his to chip his way back into the black!